An international research team has discovered marine bacteria dramatically increase their use of solar energy during massive phytoplankton blooms. The finding reveals a previously overlooked energy pathway in the ocean’s most productive periods. Led by scientist Laura Gómez-Consarnau, the study was published this week in the journal Nature Communications.

The research demonstrates that microbial proteins, not involved in traditional photosynthesis, reach peak concentrations precisely when phytoplankton growth explodes. This process provides a significant energy boost to bacteria responsible for breaking down organic matter. The work fundamentally alters how scientists view energy flow in marine ecosystems, with direct implications for understanding the global carbon cycle.

Tracking Light Capture in a Productive Ocean

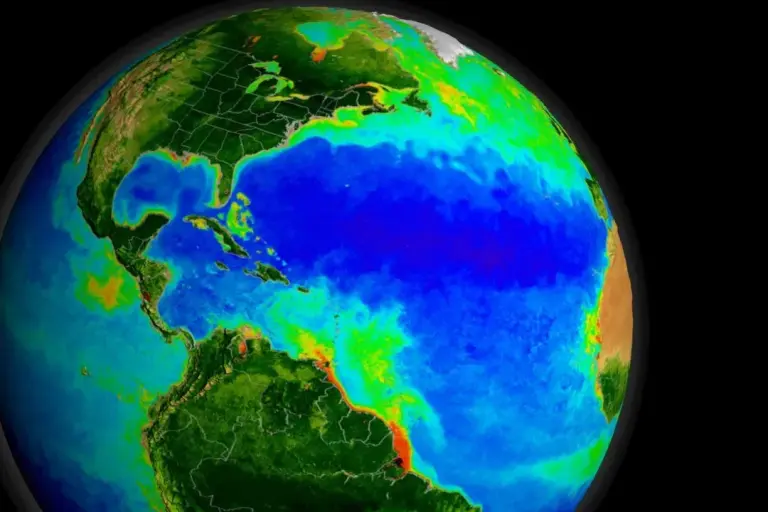

Scientists conducted the investigation in the coastal upwelling system off California. This region experiences intense spring phytoplankton blooms when winds push nutrient-rich deep water to the surface. The team performed monthly sampling for over a year, moving beyond genetic analysis to directly measure retinal. Retinal is the active molecule in light-capturing proteins called microbial rhodopsins.

This direct measurement allowed researchers to quantify exactly how many light-harvesting systems were active in the seawater. They discovered rhodopsin concentrations surged up to ninefold during bloom events. That increase perfectly coincided with peaks in chlorophyll and overall biological productivity.

“Understanding how solar energy is used in these environments is fundamental for improving models of the carbon cycle and its relationship with climate,” the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Studies (IMEDEA) stated in a release. [Translated from Spanish]

The spike in solar energy use was tightly linked to a proliferation of specific heterotrophic bacteria, particularly the Flavobacteriales group. These microbes are known for degrading organic material produced by phytoplankton. The study estimates roughly 70 percent of heterotrophic bacteria present during blooms contained rhodopsins.

A New Metabolic Strategy for Ocean Bacteria

This widespread mechanism suggests a common survival strategy. Bacteria appear to use solar energy as a metabolic supplement while consuming organic compounds from the bloom. It could enable more efficient processing of organic matter in the sunlit surface ocean.

The discovery expands the known role of microbial rhodopsins from nutrient-poor oceans to the planet’s most fertile waters. It shows microscopic marine life combines multiple strategies to exploit solar energy. Coastal upwelling regions like the study area contribute a massive share of global marine biological production. A fuller picture of their energy dynamics is therefore critical.

“Light capture by bacteria represents an additional input of energy into marine ecosystems, little considered until now,” the authors emphasized. [Translated from Spanish] They noted this energy “can influence the speed and efficiency with which organic matter is recycled in the ocean.”

These results reinforce a growing consensus. The ocean’s energy machinery is far more complex than traditional models suggest. Bacteria act not just as recyclers of organic material but also as active agents in harvesting solar power. Their dual role makes them a pivotal component in marine biogeochemical cycles.

Researchers are now expanding this line of inquiry into the Mediterranean Sea from the IMEDEA lab. They are analyzing year-round rhodopsin-based energy capture and its impact on oceanic cycles. This ongoing work combines measurements of rhodopsin levels with characterization of changes in the marine metabolome.

New infrastructure at the center, including a recently acquired Thermo Fisher Orbitrap Exploris 120 mass spectrometer, enables this detailed analysis. The team aims to integrate these microbial energy pathways into broader climate models. Accurate predictions require understanding every flux of energy and matter, a task that is fundamentally part of building a resilient future. The microscopic world, it turns out, holds some of the biggest keys to understanding planetary systems.