A long-awaited trial for one of Latin America’s largest corruption scandals is scheduled to start in Panama City on Monday, January 12, 2026. Prosecutors will present their case against 31 individuals accused of orchestrating a vast bribery scheme with the Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht. This proceeding represents a pivotal test for Panama’s judicial system after more than a decade of investigations and five previous failed attempts to begin the trial.

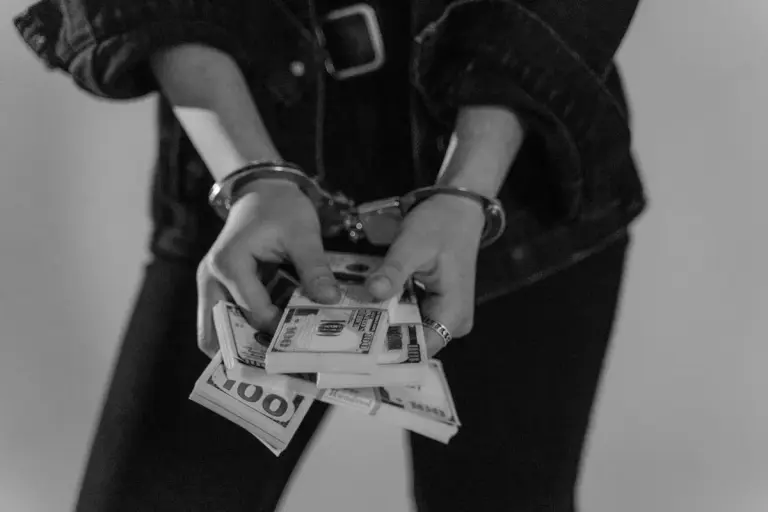

The case centers on allegations that Odebrecht paid over $59 million in bribes to Panamanian officials and political operatives between 2010 and 2014. These payments were allegedly made to secure lucrative public works contracts. The start date now faces a fresh challenge, however, as a last-minute legal motion seeks another postponement.

Final Hurdle Before the Gavel Falls

Former Minister of the Presidency Demetrio Papadimitriu filed an appeal for constitutional protections on January 5. His lawyer, Arturo Vicente Sauri Muñoz, presented the motion to the First Superior Tribunal, where it is now before Judge Janeth Torres. The appeal challenges a May 2025 court order that formally called Papadimitriu and 30 others to stand trial.

Papadimitriu’s defense argues the trial would subject him to double jeopardy. Judicial authorities have not yet suspended the Monday start date pending a ruling on this final motion. Lead prosecutor Ruth Morcillo remains prepared to proceed on behalf of the Public Ministry.

“The judicial branch maintains the date of Monday, January 12 for the start of the hearing,” a court official confirmed. [Translated from Spanish]

This latest delay tactic underscores the entrenched challenges Panama has faced in bringing this case to court. The trial has been suspended at least five times since it was first scheduled in July 2024. Previous postponements were caused by medical certificates, absent defendants, and incomplete documentation from Brazilian authorities.

The Anatomy of a Continent-Wide Scandal

The Odebrecht scandal unraveled a hemisphere-wide network of graft. In Panama, investigators from the Special Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office traced a complex money trail. They found bribes were funneled through a secret division within Odebrecht known as the “Structured Operations Division.”

This unit, nicknamed “Box 2,” used shell companies, offshore accounts, and front men to disguise illegal payments. The primary charge at trial will be money laundering. Prosecutors allege the defendants used Panama’s financial system to conceal and move funds originating from bribes.

“The main crime to be tried is money laundering, for the use of the financial system to conceal and mobilize funds from bribes,” the prosecution’s charging document states. [Translated from Spanish]

High-Profile Defendants Await Their Day in Court

The list of those called to trial reads like a who’s who of recent Panamanian political power. It includes former ministers, ex-legislators, and senior officials from the 2010-2014 period. Key figures facing charges are Demetrio Papadimitriu, former Minister of the Presidency, and Jaime Ford, a former Minister of Public Works.

Other notable defendants are former Public Works Minister Federico José Suárez, former Housing Minister José Domingo Arias, and former Economy Minister Frank De Lima. The investigation also implicates two former presidents, ricardo martinelli and juan carlos varela.

Due to their status, Martinelli and Varela must be tried separately by the Supreme Court of Justice. That same corte suprema holds jurisdiction over Martinelli’s two sons, Ricardo Alberto and Luis Enrique Martinelli Linares, because they served as regional parliamentarians.

Major Infrastructure Projects Built on Bribes

The bribery scheme secured Odebrecht some of the most significant public contracts in modern Panama. Projects named in the indictment include the second phase of the Cinta Costera coastal beltway, the Bay of Panama Sanitation Project, and the Madden-Colón Highway. The urban renewal of Curundú, the Colon renovation, and Lines 1 and 2 of the Panama Metro also feature prominently.

Investigators documented systematic overbilling and inflated costs. In the Curundú project, for instance, prosecutors found evidence that pipes were declared as imported at high prices. They were actually purchased locally at a much lower cost. The difference, investigators allege, was siphoned off to intermediaries in the bribery network.

This trial will force a public accounting for that era of breakneck infrastructure development. Citizens have waited years to see accountability for a scandal that distorted national spending and undermined public trust. Its commencement, if it finally happens, will be watched closely across a region still grappling with the fallout from Odebrecht’s corrupt practices.